Alaska contains the

largest coastal mountain range in

the world and the highest peak in North America. It has more coastline

than the entire contiguous 48 states combined and is big enough to hold

the state of Texas two and a half times over. It has the largest

population of bald eagles in the country. It has 430 kinds of birds

along with the brown bear, the largest carnivorous land mammal in the

world, and other species ranging from the pygmy shrew that weighs less

than a penny to gray whales that come in at 45 tons. Species that are

classified as “endangered” in other places are often found in abundance

in Alaska.

Now, a dozen years after I left my home state and

landed in Baghdad to begin life as a journalist and nine years after

definitively abandoning Alaska, I find myself back. I wish it was to

climb another mountain, but this time, unfortunately, it’s because I

seem increasingly incapable of escaping the long and destructive reach

of the U.S. military.

That summer in 2003 when my life in Alaska

ended was an unnerving one for me. It followed a winter and spring in

which I found myself protesting the coming invasion of Iraq in the

streets of Anchorage, then impotently watching the televised spectacle

of the Bush administration’s “shock and awe” assault on that country as

Baghdad burned and Iraqis were slaughtered. While on Denali that summer I

listened to news of the beginnings of what would be an occupation from

hell and, in my tent on a glacier at 17,000 thousand feet, wondered what

in the world I could do.

In this way, in a cloud of angst, I

traveled to Iraq as an independent news team of one and found myself

reporting on atrocities that were evident to anyone not embedded with

the U.S. military, which was then laying waste to the country. My early

reporting, some of it for

TomDispatch, warned of

body counts on

a trajectory toward one million, rampant torture in the military’s

detention facilities, and the toxic legacy it had left in the city of

Fallujah thanks to the use of depleted uranium munitions and

white phosphorous.

As I learned, the U.S. military is an industrial-scale killing machine and also the single largest

consumer of fossil fuels on

the planet, which makes it a major source of the greenhouse gas carbon

dioxide. As it happens, distant lands like Iraq sitting atop vast

reservoirs of oil and natural gas are by no means its only

playing fields.

Take the place where I now live, the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state. The U.S. Navy already has plans to conduct

electromagnetic warfare training in

an area close to where I moved to once again seek solace in the

mountains: Olympic National Forest and nearby Olympic National Park. And

this June, it’s scheduling massive war games in the Gulf of Alaska,

including live bombing runs that will mean the detonation of tens of

thousands of pounds of toxic munitions, as well as the use of active

sonar in the most pristine, economically valuable, and sustainable

salmon fishery in the country (arguably in the world). And all of this

is to happen right in the middle of fishing season.

This time, in

other words, the bombs will be falling far closer to home. Whether it’s

war-torn Iraq or “peaceful” Alaska, Sunnis and Shi’ites or salmon and

whales, to me the omnipresent “footprint” of the U.S. military

feels inescapable.

The War Comes Home

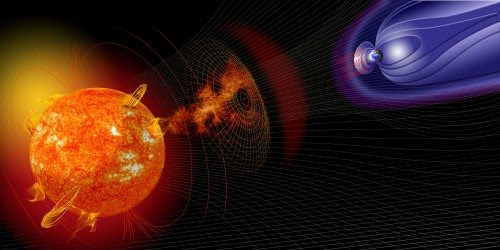

In 2013, U.S. Navy researchers

predicted ice-free

summer Arctic waters by 2016 and it looks as if that prediction might

come true. Recently, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA)

reported that

there was less ice in the Arctic this winter than in any other winter

of the satellite era. Given that the Navy has been making plans for

“ice-free” operations in the Arctic since

at least 2001,

their June “Northern Edge” exercises may well prove to be just the

opening salvo in the future northern climate wars, with whales, seals,

and salmon being the first in the line of fire.

In April 2001, a

Navy symposium entitled “Naval Operations in an Ice-Free Arctic” was

mounted to begin to prepare the service for a climate-change-induced

future. Fast forward to June 2015. In what the military refers to as

Alaska’s “premier” joint training exercise, Alaskan Command aims to

conduct “Northern Edge” over 8,429 nautical miles, which include

critical habitat for all five wild Alaskan salmon species and 377 other

species of marine life. The upcoming war games in the Gulf of Alaska

will not be the first such exercises in the region—they have been

conducted, on and off, for the last 30 years—but they will be the

largest by far. In fact, a 360% rise in munitions use is expected,

according to Emily Stolarcyk, the program manager for the Eyak

Preservation Council (EPC).

The waters in the Gulf of Alaska are

some of the most pristine in the world, rivaled only by those in the

Antarctic, and among the purest and most nutrient-rich waters anywhere.

Northern Edge will take place in an Alaskan “marine protected area,” as

well as in a NOAA-designated “fisheries protected area.” These war games

will also coincide with the key breeding and migratory periods of the

marine life in the region as they make their way toward Prince William

Sound, as well as further north into the Arctic.

Species affected

will include blue, fin, gray, humpback, minke, sei, sperm, and killer

whales, the highly endangered North Pacific right whale (of which there

are only approximately 30 left), as well as dolphins and sea lions. No

fewer than a dozen native tribes including the Eskimo, Eyak, Athabascan,

Tlingit, Sun’aq, and Aleut rely on the area for subsistence living, not

to speak of their cultural and spiritual identities.

The Navy is

already permitted to use live ordnance including bombs, missiles, and

torpedoes, along with active and passive sonar in “realistic” war gaming

that is expected to involve the release of as much as 352,000 pounds of

“expended materials” every year. (The Navy’s EIS

lists numerous

things as “expended materials,” including missiles, bombs, torpedoes.)

At present, the Navy is well into the process of securing the necessary

permits for the next five years and has even mentioned making plans for

the next 20. Large numbers of warships and submarines are slated to move

into the area and the potential pollution from this has worried

Alaskans who live nearby.

“We are concerned about expended

materials in addition to the bombs, jet noise, and sonar,” the Eyak

Preservation Council’s Emily Stolarcyk tells me as we sit in her office

in Cordova, Alaska. EPC is an environmental and social-justice-oriented

nonprofit whose primary mission is to protect wild salmon habitat.

“Chromium, lead, tungsten, nickel, cadmium, cyanide, ammonium

perchlorate, the Navy’s own

environmental impact statement says there is a high risk of chemical exposure to fish.”

Tiny

Cordova, population 2,300, is home to the largest commercial fishing

fleet in the state and consistently ranks among the top 10 busiest U.S.

fishing ports. Since September, when Stolarcyk first became aware of the

Navy’s plans, she has been working tirelessly, calling local, state and

federal officials and alerting virtually every fisherman she runs into

about what she calls “the storm” looming on the horizon. “The

propellants from the Navy’s missiles and some of their other weapons

will release benzene, toluene, xylene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,

and naphthalene into the waters of twenty percent of the training area,

according to their own EIS [environmental impact statement],” she

explains as we look down on Cordova’s harbor with salmon fishing season

rapidly approaching. As it happens, most of the chemicals she mentioned

were part of BP’s disastrous 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, which

I

covered for years, so as I listened to her I had an eerie sense of futuristic

déjà vu.

Here’s

just one example of the kinds of damage that will occur: the cyanide

discharge from a Navy torpedo is in the range of 140-150 parts per

billion. The Environmental Protection Agency’s “allowable” limit on

cyanide: one part per billion.

The Navy’s EIS estimates that, in

the five-year period in which these war games are to be conducted, there

will be more than 182,000 “takes”—direct deaths of a marine mammal, or

the disruption of essential behaviors like breeding, nursing, or

surfacing. On the deaths of fish, it offers no estimates at all.

Nevertheless, the Navy will be permitted to use at least 352,000 pounds

of expended materials in these games annually. The potential negative

effects could be far-reaching, given species migration and the global

current system in northern waters.

In the meantime, the Navy is

giving Stolarcyk’s efforts the cold shoulder, showing what she calls

“total disregard toward the people making their living from these

waters.” She adds, “They say this is for national security. They are

theoretically defending us, but if they destroy our food source and how

we make our living, while polluting our air and water, what’s left

to defend?”

Stolarcyk has been labeled an “activist” and

“environmentalist,” perhaps because the main organizations she’s managed

to sign on to her efforts are indeed environmental groups like the

Alaska Marine Conservation Council, the

Alaska Center for the Environment, and the

Alaskans First Coalition.

“Why

does wanting to protect wild salmon habitat make me an activist?” she

asks. “How has that caused me to be branded as an environmentalist?”

Given that the Alaska commercial fishing industry could be decimated if

its iconic “wild-caught” salmon turn up with traces of cyanide or any of

the myriad chemicals the Navy will be using, Stolarcyk could as easily

be seen as fighting for the well-being, if not the survival, of the

fishing industry in her state.

War Gaming the Community

The

clock is ticking in Cordova and others in Stolarcyk’s community are

beginning to share her concerns. A few like Alexis Cooper, the executive

director of

Cordova District Fishermen United (CDFU),

a non-profit organization that represents the commercial fishermen in

the area, have begun to speak out. “We’re already seeing reduced numbers

of halibut without the Navy having expanded their operations in the GOA

[Gulf of Alaska],” she says, “and we’re already seeing other decreases

in harvestable species.”

CDFU represents more than 800 commercial

salmon fishermen, an industry that accounts for an estimated 90% of

Cordova’s economy. Without salmon, like many other towns along coastal

southeastern Alaska, it would effectively cease to exist.

Teal

Webber, a lifelong commercial fisherwoman and member of the Native

Village of Eyak, gets visibly upset when the Navy’s plans come up. “You

wouldn’t bomb a bunch of farmland,” she says, “and the salmon run comes

right through this area, so why are they doing this now?” She adds,

“When all of the fishing community in Cordova gets the news about how

much impact the Navy’s war games could have, you’ll see them oppose it

en masse.”

While

I’m in town, Stolarcyk offers a public presentation of the case against

Northern Edge in the elementary school auditorium. As she shows a

slide from the Navy’s environmental impact statement indicating that the

areas affected will take decades to recover, several fishermen quietly

shake their heads.

One of them, James Weiss, who also works for

Alaska’s Fish and Game Department, pulls me aside and quietly says, “My

son is growing up here, eating everything that comes out of the sea. I

know fish travel through that area they plan to bomb and pollute, so of

course I’m concerned. This is too important of a fishing area to put

at risk.”

In the question-and-answer session that follows, Jim Kasch, the

town’s mayor, assures Stolarcyk that he’ll ask the city council to

become involved. “What’s disturbing is that there is no thought about

the fish and marine life,” he tells me later. “It’s a sensitive area and

we live off the ocean. This is just scary.” A Marine veteran, Kasch

acknowledges the Navy’s need to train, then pauses and adds, “But

dropping live ordnance in a sensitive fishery just isn’t a good idea.

The entire coast of Alaska lives and breathes from our resources from

the ocean.”

That evening, with the sun still high in the spring

sky, I walk along the boat docks in the harbor and can’t help but wonder

whether this small, scruffy town has a hope in hell of stopping or

altering Northern Edge. There have been examples of such unlikely

victories in the past. A dozen years ago, the Navy was, for example,

finally

forced to stop using the

Puerto Rican island of Vieques as its own private bombing and test

range, but only after having done so since the 1940s. In the wake of

those six decades of target practice, the island’s population has the

highest cancer and asthma rates in the Caribbean, a phenomenon locals

attribute to the Navy’s activities.

Similarly, earlier this year a

federal court ruled that

Navy war games off the coast of California violated the law. It deemed

an estimated 9.6 million “harms” to whales and dolphins via

high-intensity sonar and underwater detonations improperly assessed as

“negligible” in that service’s EIS.

As a result of Stolarcyk’s work, on May 6th Cordova’s city council

passed a resolution formally opposing the upcoming war games. Unfortunately, the largest seafood processor in Cordova (and Alaska),

Trident Seafoods,

has yet to offer a comment on Northern Edge. Its representatives

wouldn’t even return my phone call on the subject. Nor, for instance,

has Cordova’s

Prince William Sound Science Center,

whose president, Katrina Hoffman, wrote me that “as an organization, we

have no position statement on the matter at this time.” This, despite

their stated aim of supporting “the ability of communities in this

region to maintain socioeconomic resilience among healthy, functioning

ecosystems.” (Of course, it should be noted that at least some of their

funds come from the

Navy.)

Government-to-Government Consultation

At

Kodiak Island, my next stop, I find a stronger sense of the threat on

the horizon in both the fishing and tribal communities and palpable

anger about the Navy’s plans. Take J.J. Marsh, the CEO of the Sun’aq

Tribe, the largest on the island. “I think it’s horrible,” she says the

minute I sit down in her office. “I grew up here. I was raised on

subsistence living. I grew up caring about the environment and the

animals and fishing in a native household living off the land and seeing

my grandpa being a fisherman. So obviously, the need to protect this

is clear.”

What, I ask, is her tribe going to do?

She

responds instantly. “We are going to file for a government-to-government

consultation and so are other Kodiak tribes so that hopefully we can

get this stopped.”

The U.S. government has a unique relationship

with Alaska’s Native tribes, like all other American Indian tribes. It

treats each as if it were an

autonomous government.

If a tribe requests a “consultation,” Washington must respond and

Marsh hopes that such an intervention might help block Northern Edge.

“It’s about the generations to come. We have an opportunity as a

sovereign tribe to go to battle on this with the feds. If we aren’t

going to do it, who is?”

Melissa Borton, the tribal administrator

for the Native Village of Afognak, feels similarly. Like Marsh’s tribe,

hers was, until recently, remarkably unaware of the Navy’s plans.

That’s hardly surprising since that service has essentially made

no effort to

publicize what it is going to do. “We are absolutely going to be part

of this [attempt to stop the Navy],” she tells me. “I’m appalled.”

One reason she’s appalled: she lived through Alaska’s monster

Exxon Valdez oil spill of

1989. “We are still feeling its effects,” she says. “Every time they

make these environmental decisions they affect us… We are already

plagued with cancer and it comes from the military waste already in our

ground or that our fish and deer eat and we eat those… I’ve lost family

to cancer, as most around here have and at some point in time this has

to stop.”

When I meet with Natasha Hayden, an Afognak tribal

council member whose husband is a commercial fisherman, she puts the

matter simply and bluntly. “This is a frontal attack by the Navy on our

cultural identity.”

Gary Knagin, lifelong fisherman and member of

the Sun’aq tribe, is busily preparing his boat and crew for the salmon

season when we talk. “We aren’t going to be able to eat if they do this.

It’s bullshit. It’ll be detrimental to us and it’s obvious why. In

June, when we are out there, salmon are jumping [in the waters] where

they want to bomb as far as you can see in any direction. That’s the

salmon run. So why do they have to do it in June? If our fish are

contaminated, the whole state’s economy is hit. The fishing industry

here supports everyone and every other business here is reliant upon the

fishing industry. So if you take out the fishing, you take out

the town.”

The Navy’s Free Ride

I requested

comment from the U.S. military’s Alaskan Command office, and Captain

Anastasia Wasem responded after I returned home from my trip north. In

our email exchange, I asked her why the Navy had chosen the Gulf of

Alaska, given that it was a critical habitat for all five of the state’s

wild salmon. She replied that the waters where the war games will

occur, which the Navy refers to as the Temporary Maritime Activities

Area, are “strategically significant” and claimed that a recent “Pacific

command study” found that naval training opportunities are declining

everywhere in the Pacific “except Alaska,” which she referred to as “a

true national asset.”

“The Navy’s training activities,” she added,

“are conducted with an extensive set of mitigation measures designed to

minimize the potential risk to marine life.”

In its assessment of

the Navy’s plans, however, the National Marine Fisheries Service

(NMFS), one of the premier federal agencies tasked with protecting

national fisheries, disagreed. “Potential stressors to managed species

and EFH [essential fish habitat],” its

report said,

“include vessel movements (disturbance and collisions), aircraft

overflights (disturbance), fuel spills, ship discharge, explosive

ordnance, sonar training (disturbance), weapons firing/nonexplosive

ordnance use (disturbance and strikes), and expended materials

(ordnance-related materials, targets, sonobuoys, and marine markers).

Navy activities could have direct and indirect impacts on individual

species, modify their habitat, or alter water quality.” According to the

NMFS, effects on habitats and communities from Northern Edge “may

result in damage that could take years to decades from which

to recover.”

Captain Wasem assured me that the Navy made its plans

in consultation with the NMFS, but she failed to add that those

consultations were found to be inadequate by the agency or to

acknowledge that it expressed serious concerns about the coming war

games. In fact, in 2011 it made four conservation recommendations to

avoid, mitigate, or otherwise offset possible adverse effects to

essential fish habitat. Although such recommendations were non-binding,

the Navy was supposed to consider the public interest in its planning.

One

of the recommendations, for instance, was that it develop a plan to

report on fish mortality during the exercises. The Navy rejected this,

claiming that

such reporting would “not provide much, if any, valuable data.” As

Stolarcyk told me, “The Navy declined to do three of their four

recommendations, and NMFS just rolled over.”

I asked Captain Wasem why the Navy choose to hold the exercise in the middle of salmon fishing season.

“The

Northern Edge exercise is scheduled when weather is most conducive for

training,” she explained vaguely, pointing out that “the Northern Edge

exercise is a big investment for DoD [the Department of Defense] in

terms of funding, use of equipment/fuels, strategic transportation,

and personnel.”

Arctic Nightmares

The

bottom line on all this is simple, if brutal. The Navy is increasingly

focused on possible future climate-change conflicts in the melting

waters of the north and, in that context, has little or no intention of

caretaking the environment when it comes to military exercises. In

addition, the federal agencies tasked with overseeing any war-gaming

plans have neither the legal ability nor the will to enforce

environmental regulations when what’s at stake, at least according to

the Pentagon, is “national security.”

Needless to say, when it

comes to the safety of locals in the Navy’s expanding area of operation,

there is no obvious recourse. Alaskans can’t turn to NMFS or the

Environmental Protection Agency or NOAA. If you want to stop the U.S.

military from dropping live munitions, or blasting electromagnetic

radiation into national forests and marine sanctuaries, or poisoning

your environment, you’d better figure out how to file a major lawsuit

or, if you belong to a Native tribe, demand a government-to-government

consultation and hope it works. And both of those are long shots,

at best.

Meanwhile, as the race heats up for reserves of oil and

gas in the melting Arctic that shouldn’t be extracted and burned in the

first place, so do the Navy’s war games. From southern California to

Alaska, if you live in a coastal town or city, odds are that the Navy is

coming your way, if it’s not already there.

Nevertheless, Emily

Stolarcyk shows no signs of throwing in the towel, despite the way the

deck is stacked against her efforts. “It’s supposedly our constitutional

right that control of the military is in the hands of the citizens,”

she told me in our last session together. At one point, she paused and

asked, “Haven’t we learned from our past mistakes around not protecting

salmon? Look at California, Oregon, and Washington’s salmon. They’ve

been decimated. We have the best and most pristine salmon left on the

planet, and the Navy wants to do these exercises. You can’t have both.”

Stolarcyk

and I share a bond common among people who have lived in our

northernmost state, a place whose wilderness is so vast and beautiful as

to make your head spin. Those of us who have experienced its rivers and

mountains, have been awed by the northern lights, and are regularly

reminded of our own insignificance (even as we gained a new appreciation

for how precious life really is) tend to want to protect the place as

well as share it with others.

“Everyone has been telling me from

the start that I’m fighting a lost cause and I will not win,” Stolarcyk

said as our time together wound down. “No other non-profit in Alaska

will touch this. But I actually believe we can fight this and we can

stop them. I believe in the power of one. If I can convince someone to

join me, it spreads from there. It takes a spark to start a fire, and I

refuse to believe that nothing can be done.”

Three decades ago, in his book

Arctic Dreams,

Barry Lopez suggested that, when it came to exploiting the Arctic

versus living sustainably in it, the ecosystems of the region were too

vulnerable to absorb attempts to “accommodate both sides.” In the years

since, whether it’s been the Navy, Big Energy, or the increasingly

catastrophic impacts of human-caused climate disruption, only one side

has been accommodated and the results have been dismal.

In Iraq

in wartime, I saw what the U.S. military was capable of in a distant

ravaged land. In June, I’ll see what that military is capable of in what

still passes for peacetime and close to home indeed. As I sit at my

desk writing this story on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, the roar of

Navy jets periodically rumbles in from across Puget Sound where a

massive naval air station is located. I can’t help but wonder whether,

years from now, I’ll still be writing pieces with titles like

“Destroying What Remains,” as the Navy continues its war-gaming in an

ice-free summer Arctic amid a sea of off-shore oil drilling platforms.