Saying goodbye to Apple and Microsoft has never been easier, or so satisfying

On a spring day in 2012, I shut down my MacBook Air for the last time. From then on, my primary computing environment — at least on a laptop computer — was GNU/Linux.

I was abandoning, as much as possible, the proprietary,

control-freakish environments that Apple and Microsoft have increasingly

foisted on users of personal computers.

Almost

four years later, here I am, writing this piece on a laptop computer

running the Linux* operating system and LibreOffice Writer, not on a Mac

or Windows machine using Microsoft Word. All is well.

No, better than that — everything’s terrific.

I’d

recommend this move to lots of folks — not everyone, by any means, but

to anyone who isn’t afraid to ask some occasional questions, and

especially anyone who gives some thought to the trajectory of technology

and communications in the 21st Century. Most of all, to people who care

about freedom.

Personal

computing dates back to the late 1970s. It defined an era of technology

when users could adapt what they’d purchased in all kinds of ways. When

mobile computing came along in the form of smart phones, the balance

shifted; the sellers, especially Apple, retained significantly more

control. They’ve given us more convenience, and we’ve collectively said,

“Great!”

A few months ago, when Apple introduced its iPad Pro, a large tablet with a keyboard, CEO Tim Cook called it the “clearest expression of our vision of the future of personal computing.”

That was an uh-oh moment for me. Among other things, in the iOS

ecosystem users are obliged to get all their software from Apple’s

store, and developers are obliged to sell it in the company store. This

may be Apple’s definition of personal computing, but it’s not mine.

Meanwhile,

Microsoft’s Windows 10 — by almost all accounts a huge usability

improvement over Windows 8 — looks more and more like spyware masquerading as an operating system (a characterization that may be unfair, but not by much).

Yes, the upgrade from widely installed earlier versions is “free” (as

in beer), but it takes some amazing liberties with users’ data and

control, according to people who’ve analyzed its inner workings.

It’s

not quite a commercial duopoly. Google’s Chrome operating system is

powering a relatively new entrant: the Chromebook sold by various

manufacturers. But it comes with more limitations, and requires users to

be totally comfortable — I’m not — in the embrace of a company that

relies on surveillance to support its advertising-based business model.

So

for anyone who’s even slightly interested in retaining significant

independence in desktop and laptop computing, Linux is looking like the

last refuge. (On an assortment of other devices, from supercomputers to

servers to mobile phones to embedded systems, Linux is already a powerhouse.) I’m glad I made this move.

Before I explain how, it’s vital to recognize

the overall context of my small rebellion. Re-centralization is the new

normal in technology and communications, a trend I worried about here

some time ago, when I described in a more general way how I was trying to wean myself off services and products

from companies like Apple (done), Microsoft (mostly done) and Google

(still difficult). Convenience, I said at the time, wasn’t worth the

tradeoffs we’re making.

As

I’ll discuss later, I also have to wonder how much it matters to

declare independence on a personal computer, since computing is moving

more and more onto mobile devices. Like it or not, Apple and Google have

pretty much taken charge of those with the iOS and Android. Apple, as

noted, is a relentless control freak. Even though Google gives away an

open version of Android, more and more of the most essential pieces of

that operating system are part of a highly proprietary software blob

that still ties users into Google’s advertising-driven world. Can you

say mobile “duopoly?”

The

re-centralization is particularly scary given the growing power of the

telecommunications industry, which is fighting tooth and nail to control

what you and I can do with the connections we pay for, despite the

FCC’s welcome ruling in favor of “network neutrality” in 2015. Comcast

is a monopoly for true broadband service in most of its territories,

though you can spot a few competitors here and there. The cable ISPs are

moving swiftly to impose usage caps that have nothing to do with

capacity and everything to do with extending their power and profits, as Susan Crawford has explained in detail. And mobile carriers are outright defying network neutrality with “zero-rated” services the FCC inexplicably calls innovative.

Meanwhile,

because users so often prefer convenience and hidden subsidies to their

own long-term liberties, centralized players like Facebook are

assembling unprecedented monopolies. Like Google in search, they are

reaping the expanding benefits of network effects that competitors will

find difficult if not impossible to challenge.

Let’s

not forget government, which absolutely loathes decentralization.

Centralized services create choke points, and make life easier for law

enforcement, spies, regulators and tax collectors. The surveillance state loves data-collection choke points that ultimately put everyone’s communications, and liberty, at risk.

Choke

points also make it easier to help prop up corporate business models in

ways that generate lots of campaign cash for the politicians. Hollywood

is a prime example; the copyright cartel’s near-ownership of Congress

has led to absurd and deeply restrictive laws like our current copyright

system.

Copyright is key to what my friend Cory Doctorow has called the “coming civil war over general purpose computing,”

a campaign, sometimes overt, to prevent the people who buy gear — you

and me, individually and in our schools, businesses, and other

organizations — from actually owning it. Copyright law is the control

freaks’ leverage, because it allows them to legally prevent us from

tinkering (they’d say tampering) with what they sell.

The

trends aren’t all bad. The “maker” movement of the past few years is

one of the antidotes to this control freakery. So are key components of

many maker projects: free (as in freedom) and open-source software

projects where users are specifically entitled to modify and copy the

code.

That’s

where Linux comes in. Even though we’re doing more on mobile devices,

hundreds of millions of us still do a lot with desktops and laptops.

Linux and other community-built software may be just a partial solution,

but they’re definitely a useful one. Better to start somewhere, and

work beyond that, than to give up.

I’ve installed Linux a number of times

over the years since it first became a real operating system. But I

always went back either to Windows or the Mac, depending on which was my

main system at the moment. Why? There were too many rough edges, and

for a long time Linux didn’t have enough applications to do what I

needed. The complications were too much for my limited patience in

everyday use.

But it got better and better, and in 2012, I decided it was time. I asked Cory which version of Linux he was using. This was a key question, because Linux comes in a lot of different flavors. Developers have taken the core code and created different versions tailored to various needs, tastes and computing styles. While all use the essential, free-software base components, some add on proprietary code, such as Flash, to be more compatible with what users are likely to encounter in their computing. The hardware was also a key question, because not all computers have robust Linux support due to hardware incompatibilities.

Cory told me he was using Ubuntu, on a Lenovo ThinkPad.

I was already sold on ThinkPads, due to the hardware’s sturdiness and

solid service from the manufacturer, not to mention the ability to

upgrade the internal hardware. Because I tend to buy newer models, I

sometimes run into issues with support for Lenovo’s latest hardware.

I’ve tricked out my current model, a T450s, in any number of ways, such

as replacing the mechanical hard disk with a fast SSD drive and adding

as much RAM memory as I can fit into the device.

I

was also leaning toward Ubuntu, a Linux version created by a company

called Canonical, which is headed by a former software entrepreneur

named Mark Shuttleworth, whom I’ve also known for some time. Ubuntu is

known for its excellent support of ThinkPads, especially if they’re not

brand new. I’ve run Ubuntu on four different ThinkPads since switching.

Ubuntu is also an acquired taste because Canonical has a distinct vision

of how things should work.

So

you might want to try a different Linux “distribution,” as the various

flavors are called. There are too many to mention, which is

simultaneously one of the best and worst features of the Linux

ecosystem. New users should almost certainly try one of the more popular

distributions, which will have been more thoroughly tested and will

have better support from the community and/or company that created it.

One of those is Linux Mint. It’s based on Ubuntu (which in turn is based on Debian, an even more core version of Linux). Mint strikes me and many others as perhaps the best Linux for people who’ve been using proprietary systems and want the easiest possible transition. I’m sometimes tempted to switch myself, but will stick with Ubuntu unless Canonical totally screws it up, which I don’t expect.

Before

I made the jump I asked a number of people for advice on how best to

migrate my computing from proprietary to open-source programs. Several

suggested what turned out to be a helpful move: I ditched Apple Mail and

installed Mozilla’s Thunderbird

email software on my Mac, and over a month or so got fully accustomed

to its different, yet not too different, way of handling my mail. (No, I

don’t use Gmail except as a spare account.) I also installed LibreOffice, an open semi-clone of Microsoft Office, which was quirkier but adequate for most purposes.

Like

most people using personal computers, my time is spent almost entirely

in just a few applications: web browser, email, word processor. For

Linux browsers I installed Firefox and Chromium,

an open-source variant on Google’s Chrome. As noted, Thunderbird served

nicely for email, and LibreOffice was okay for word processing.

But

I still needed to run Windows for several purposes. In particular, the

online-course software I was using at my university refused to work with

Linux in any browser. So I installed Windows in a “virtual machine,” a

way of running Windows and its programs from inside Linux. (I also

loaded Windows on a separate internal solid-state drive for the even

more rare occasions when I’d need to run it natively, as opposed to in a

virtual machine that reduces performance.)

Today

I almost never need Windows. LibreOffice has improved a great deal. For

cloud-based editing Google Docs (cough; I did say leaving Google is

difficult) is hard to beat, but LibreOffice is making progress there.

The software my university uses for online courses now supports Linux

in the browser. The one program I still occasionally need to run in

Windows is Camtasia, for “screencasting” — recording what’s on the

screen, plus audio. Several Linux screencasting programs

work for bare-bones jobs. And once in a while, I’m obliged to load

Microsoft PowerPoint to read slide decks that bork in the LibreOffice

presentation software.

Oddly,

the most difficult early part of the transition was adjusting to new

keyboard conventions: unlearning the Apple style and re-learning the

Windows combinations that are, for the most part, common to Linux. After

a couple of months it all came naturally.

One

of the things I like best about Linux is the frequency of software

updates. Ubuntu and many other versions regularly offer upgrades, though

I tend to stick with what Ubuntu calls “long term support” or LTS

versions. And they are very quick to update when security flaws are

found. Hardly a week goes by without security fixes for the operating

system or accompanying software applications— much more timely than I

was used to seeing from Apple.

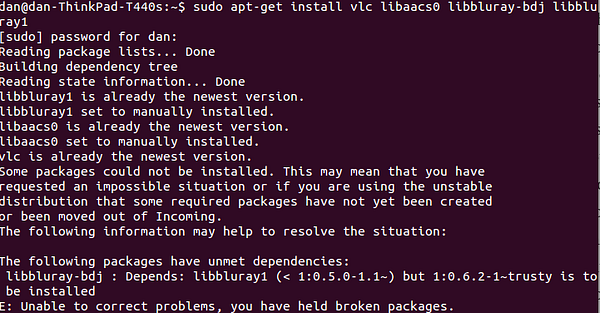

What I like least about Linux is the occasional need to do something that would be downright daunting to a new user. No one should ever have to open a command-line window and type “sudo apt-get update” or other such instructions. No one should be confronted with a warning that space on a disk partition is too low to permit an operating system update, requiring the not-simple-for-novices removal of out-of-date OS components. No one should discover, after an update, that a piece of hardware has stopped working, as was the case for me when my computer’s trackpad went south until I found a fix in an online forum. (Yes, this can happen with Windows, but manufacturers go to much greater lengths to ensure that their hardware works with Microsoft software. Apple, too, has external hardware issues, but its elegant marriage of hardware and software remains a compelling advantage.)

When problems occur, the communities that have emerged around free and open-source software are incredibly helpful.

Because I tend to push the edges somewhat in my adoption of this stuff,

I’m often asking for help. I always get it. Some super-experts in these

forums can be condescending or even rude if one asks something they

consider trivial or, more reasonably, a question that could have been

answered with a bit more research. Helpfulness and occasional

intemperance are also part of Windows, Mac and mobile

ecosystems — hardcore Apple devotees can be astonishingly abusive to the

non-faithful — but there’s a special spirit among open-tech folks who

are working for the common good.

If

you’re interested in trying desktop Linux, it’s likely easy enough with

your current computer. Ubuntu and some other distributions let you

create a DVD or USB drive with the full operating system and many

applications, and boot from the external disk into a test-drive mode.

That’s a good way to find out if your hardware will work right. It

probably will if you’re not using a brand-new computer. In fact, one of

the best things about Linux is how well it works on older computers.

One solution to the Linux-installation dilemma is to buy a computer that comes with the operating system pre-installed, and gets regular updates tuned for the hardware. I’ve been pondering models from companies such as Dell, System76 and ZaReason, among others. I just visited with a company called Purism,

which is selling laptops built entirely with non-proprietary hardware

and software, or as much as can be done at this point; their Librem 13

model is very, very impressive. Purism has adapted Linux for its own

user-friendly hardware, and I’m looking forward to trying it soon.

I

travel a lot, which works in favor of a hardware company that has

service depots around the world and — this always costs extra — will

dispatch a technician to my home, office or hotel if my machine breaks.

If I give up on Lenovo (and some of its recent behavior has given me

qualms), I’ll probably look first at Dell’s Linux machines.

You

may have noticed that I’ve scarcely mentioned cost. With desktop

operating systems, I don’t need to anymore, because Microsoft and Apple

have effectively lowered the visible price of their OSes to zero. You

still pay for them when you buy the computer, of course, but even major

upgrades have become free of charge — a big change from earlier times.

In Microsoft’s case, however, “free” seems to be at the non-trivial cost

of invasive data gathering.

Application

software is a different story. You can still save a lot using free and

open source software. Next to LibreOffice, Microsoft Office still looks

expensive even though the basic “student-family” versions are quite

affordable, and lots of people use MS Office provided by their schools

or businesses.

Here’s the thing, though. I like

to pay for software, because I want to ensure, as much as possible, a)

that if I need help I’ll be able to get it, and b) that the developers

will have an incentive to keep fixing and improving it. I’d gladly pay

for well-supported Linux versions of Camtasia and Scrivener, for instance (the latter does have community-supported Linux version).

Meanwhile, I donate to projects, whether created by companies or

entirely by volunteers, whose software I use regularly. Ubuntu may be a

company making money on providing services — a popular and proven

approach in the free and open source software worlds — but I still

donate. LibreOffice gets more than my use; it gets money. Ditto other

projects.

Linux is still a second-class citizen, at least officially, when it comes to playing DVDs. You have to install software

that the entertainment cartel calls illegal in order to play the disks

you’ve purchased. (Hollywood makes Apple look like a paragon of

freedom.) Using streaming video from companies like Netflix and Amazon

can also be a hassle, though that’s gotten easier thanks to the — uh

oh — addition of digital restrictions in some browsers.

Is

all this tweaking worth the trouble? I say yes. Anything that enhances

or preserves our ability to use technology as we wish, as opposed to the

constrained ways the centralized powers want, is worth trying — and if

more of us don’t try we may assure the eventual victory of the control

freaks.

It’s almost certainly too late for Linux

to be a hugely popular desktop/laptop operating system, at least in the

developed world. But it’s not too late for enough of us to use it that

we ensure some level of computing liberty for those who want it.

What

we can do about the mobile ecosystems, beyond allowing them to capture

all personal computing, is more problematic. Third-party versions of

Android have emerged via vibrant communities of people, such as XDA Developers, who want more freedom. Ubuntu is among many in the open-source world working on mobile operating systems; it’s spent years moving toward an OS that can transcend devices. But the mobile dominance of Apple and Google is daunting.

I’m

trying as many of these mobile options as possible, with the hope that

I’ll find something good enough for daily use even if it’s not as

convenient as the big players’ walled gardens. (One of my current phones

runs an OS called Cyanogenmod.) I’ll tell you more about how this is going soon.

Meanwhile, please remember: We do have choices — we can make decisions that push the boundaries of tech freedom.

My choices lately have been to opt out of the control-freaks’ grip

wherever possible. I hope you’ll give some thought to doing the same.

Depending on how we choose, we have much to gain, and lose.

*Although it will make some people unhappy,

I’m nonetheless referring to GNU/Linux by the far more commonly used

name — just plain “Linux” — after the first reference. For more on this

issue, Wikipedians have compiled a host of relevant sources.