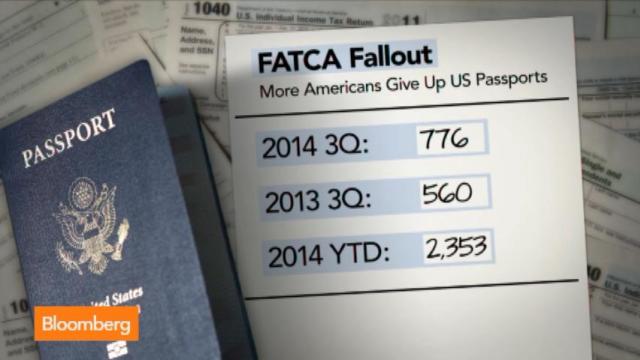

Record Number of Americans Renouncing Citizenship Because of Overseas Tax Burdens

Frustration over taxes is as American as apple pie, but some U.S. citizens are becoming so overwhelmed by the Internal Revenue Service that they’ve decided to stop being Americans altogether.

According to new Treasury Department data, 776 Americans renounced their citizenship over three months ending in September for a total of 2,353 renunciations this year, on pace to surpass the previous year’s record number of 2,999 renouncers.

Experts say this growing number of ex-Americans is a side effect of new tax regulations within the last few years intended to crack down on tax evasion but that also make it harder for all citizens abroad to conduct even routine financial transactions. Chief among them is the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, passed by Congress in 2010 and in effect since July 2014. FATCA aimed to cut down on the use of secret offshore accounts by requiring foreign banks to report all Americans with accounts over $50,000 or face a 30 percent surcharge on the accounts.

Marylouise Serrato, the executive director of American Citizens Abroad, an advocacy group, said the measure ended up hurting otherwise law-abiding citizens living in foreign countries, of which the most recent estimates say there are 6.32 million. Serrato cited a 2014 poll conducted by the group Democrats Abroad that found an average of 12.7 percent of applicants for various foreign financial services were denied by their banks.

“The problem is not paying taxes or not wanting to pay taxes, the problem is that they’re having an inability to find financial providers and people who are still willing to deal with them as American citizens,” Serrato said.

There’s also the problem of so-called “accidental Americans,” who were born in the United States but have lived most of their lives inCanada. American tax law mandates that citizens pay U.S. taxes regardless of the country in which they reside, meaning that in the last five years, when the U.S. government started cracking down on foreign tax evaders, many Canadians born in the U.S. realized for the first time that they might owe the IRS back taxes.

Among them was one man who was born in the U.S. but was brought to Canada right after birth, who insisted on anonymity because he is still in the process of renouncing his American citizenship – which he didn’t even realize he had until, on a 2011 trip south of the US-Canada border, he was told he needed an American passport in order to re-enter the United States.

He was eventually allowed to pass, but upon returning home realized the agent who let him through was correct. “Sure enough, if you are considered a US citizen you can’t travel into the US using anything other than a US passport,” he said.

He learned he could either declare five years of back taxes to the IRS under a new voluntary disclosure program, which he said would have cost him thousands of dollars in legal and accounting fees, or renounce his American citizenship, which so far has taken him more than a year and several trips to his nearest consulate to do.

“I don’t break any laws,” he said. “It’s an accident of birth.”

And when he does renounce his American citizenship, the Canada resident will also have to pay a onetime fee of $2,350 for what the State Department says is the cost of processing a citizenship renunciation.

That fee is more than a five-fold increase from what the cost was before September 2014, when renouncing one’s American citizenship cost $450.

A State Department spokesperson said the fee was increased to reflect the real, unsubsidized cost of providing the service. “In addition to the work done at the embassy or consulate, the case comes back to the department for a final review and decision, which involves additional resources. A renunciation is a serious decision, and we need to be certain that the person renouncing fully understands the consequences,” the spokesperson said via email.

Serrato’s group American Citizens Abroad recommends that Congress add a “same-country exception” to FATCA, which would exempt citizens living in a foreign country from paying a U.S. tax for financial services from a bank in the same country where they live. The intended goal would be for FATCA to affect only the groups it intended to target: potential tax evaders who live in one country but have foreign accounts in others.

“This is a community that’s not tax evaders and living the high life. There’s a real need, if the US is going to be a global player and we want Americans overseas selling products, that people need to have certain tools in order to do that,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment