Jon Ronson is ready for blast-off. Is Richard Branson?

After a 10-year wait, Richard Branson says Virgin Galactic will have lift-off this year: he and his children will be on the first (live televised) flight. What took them so long? Jon Ronson meets him and the 'future astronauts' as they prepare for the ride of their lives

It's dawn at the Mojave Air & Space Port, a cluster of weather-beaten hangars in the desert north of Los Angeles. It looks quite forlorn, in part an elephant's graveyard for half-finished prototype jets designed by visionaries who ran out of money. But it's also a gathering place for freewheeling, maverick space engineers to try out new ideas in the desert: the rocket world's wild west.

A fleet of coaches pulls up outside a hangar. The passengers, coiffured and rich-looking, climb out. The men wear shirts with logos for places such as the Monte-Carlo Polo Club. The women wear the kind of leopard print blouses you see in fashion boutiques in five-star hotels. They are led inside the hangar and take their seats.

"Welcome to the world's largest ever gathering of future astronauts," says the man on the stage, Sir Richard Branson. "As part of our wonderful, pioneering future astronaut community, your place in history is assured."

So far, nearly 700 people have paid either $200,000 or $250,000 (£125,000 or £155,000) for a two-hour trip into space inside the Virgin Galactic SpaceShipTwo, a trip that includes five minutes of weightlessness. (Virgin raised the price by $50,000 in May 2013 to adjust for inflation: some future astronauts paid their $200,000 as long ago as 2004, when tickets first went on sale and Branson predicted a 2007 launch. Tom Hanks has booked, along with Angelina Jolie and Princess Eugenie.) Four hundred of them are in Mojave today, for speeches, a cocktail party and to witness a test flight. This, unfortunately, has just been cancelled due to high winds. (It doesn't feel that windy.)

Richard Branson posing for photos with SpaceShipTwo in the Mojave desert, California, September 2013. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

Richard Branson posing for photos with SpaceShipTwo in the Mojave desert, California, September 2013. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

I'm here because the pronouncement Branson just made from the stage is probably not an exaggeration. These men and women are standing on the edge of history – pioneers in the sort-of-democratisation of space travel. Only 530 humans have been into outer space, which is defined as 100km (62 miles) above sea level. Branson is talking about putting that many people up there in his first year of operation. And it's about to happen, he says. It has been 23 years since he registered the name Virgin Galactic Airways, and 10 since they started building the spaceship – an enterprise stricken by delays and tragedy. Now they're only months away. Branson says the first unmanned test flight will take place "soon"; he and his children will take the first commercial space flight later this year.

I am at a table towards the back of the hangar, listening to the speeches with future astronaut Trevor Beattie. He's the working-class Birmingham boy who made his millions as an ad man – famous for Wonderbra's Hello Boys posters, and French Connection's FCUK campaign, as well as the 2001 and 2005 New Labour election campaigns for his friend Peter Mandelson.

"Some say Nasa sent the wrong people into space," Trevor tells me quietly. "Nasa sent scientists and engineers. When they came back, they either got God or became poets. So what happens this time, when you send creative people? Do we come back as engineers and scientists? What will it do to the other side of our brains?"

"Maybe it'll fuck you up," I whisper back.

"I talked to someone who went on the Zero G," Trevor replies. "He said that after he came back down, he found gravity a real drag."

The Zero G is a specially modified plane that, for $4,950 per passenger, creates weightlessness by performing aerobatic manoeuvres known as parabolas. Branson has been recommending that all future astronauts take a flight on it in preparation for the real thing. Trevor will take his tomorrow, 30,000ft above Burbank, California. He promises to let me know if weightlessness is all it's cracked up to be.

Now Virgin Galactic's CEO, George Whitesides, is on the stage. He surveys the room. "You are truly," he says, "the first in a new class of citizen explorer."

In the mid-80s, the then Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev invited Branson to be the first civilian in space. He asked Gorbachev's people how much it would cost – $50m, they said, "plus I'd need to spend two years training in Russia, which was too much of my time," Branson tells me. "And I thought it wouldn't look quite right somehow. Then I thought, wouldn't it be better to spend that $50m building a spaceship company instead?"

The Mojave desert north of Los Angeles is the headquarters of Branson’s space empire. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

The Mojave desert north of Los Angeles is the headquarters of Branson’s space empire. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

We're sitting in a small meeting room behind the Virgin hangar at the Mojave Air & Space Port. All this is a first for Branson. He's never created an industry from scratch before. His other endeavours have been about sprucing up existing worlds: credit cards, record labels. Not many people go from putting out the Sex Pistols to creating a new dawn for humanity. As Whitesides will later tell me, "This is the start of something really big – humanity going into the cosmos. Nasa's gone. The Russians have gone. But this is the start of the rest of us going. I really think there is a power in this moment in time in history."

So how did Branson persuade himself he could do it? "At the time we put out the Sex Pistols, people thought we were taking a giant risk," he says. "Then the train network. Each of these was a building block that gave me the confidence to dream even bigger. When I started Virgin Atlantic, I knew nothing about running airlines. I just felt somebody should be able to do it better than British Airways. By then I'd learned what a company is. A company is, you go and find the best people. We got the chief technical officer from British Caledonian, so we knew it was going to be safe, then we got a lot of creative people who weren't from the airline world to go and shake up the business. Starting a spaceship company is not that dissimilar."

The first 10 years were, he says, a fruitless trek around the world, visiting garages in the middle of nowhere to hear crazy pitches from father-and-son rocket design teams. "It was surprising how few of them really had credible, serious ideas," he says. "The biggest worry I had was re-entry. Nasa has lost about 3% of everyone who's gone into space, and re-entry has been their biggest problem. For a government-owned company, you can just about get away with losing 3% of your clients. For a private company you can't really lose anybody. Nobody we met had anything but the conventional risky re-entry mechanism that Nasa had. We were waiting for someone to come up with one that was foolproof."

He says those 10 years were frustrating, but when I ask if he ever lost his temper, he says, "Oh, I would find that very counterproductive. I was brought up by parents who, if I ever said a bad word about somebody, would send me to the mirror and make me look in it and tell me how badly it reflected on myself." He pauses. "Anyway. Finally we met Burt Rutan."

Burt Rutan is the reason for all this. If, in the coming months and years, we are all shooting up and down to outer space, we'll have Rutan to thank. In photographs, he looks rugged and outdoorsy, with country-singer hair and big sideburns. He's a legend in aerospace circles. In 1986, he built the first plane to fly around the world on a single tank of fuel. In the mid-90s, he set about trying to solve the re-entry problem.

Branson with the aerospace designer, Burt Rutan. Photograph: Bebeto Matthews/AP

Branson with the aerospace designer, Burt Rutan. Photograph: Bebeto Matthews/AP

Rutan, who is now 70, had an advantage over Nasa. If you're coming back from Mars, you re-enter the Earth's atmosphere at 12km a second. The heat and the friction at that speed can tear a machine apart. But coming back from a suborbital flight – which was the puzzle Rutan was trying to solve – the spaceship would be going a lot slower. But it would still need something to slow it down.

"Burt Rutan's idea was to turn a spaceship into a giant shuttlecock," Branson says. "And so the pilot could be sound asleep on re-entry and it didn't matter what angle it hit coming back into the Earth's atmosphere."

Rutan didn't go to Branson for funding. He went to Paul Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft. Allen was famous for lavishing money on space projects, such as the $30m he gave the Seti Institute (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) to build an array of receivers to constantly listen out for signals from other planets, so far in vain. Allen gave Rutan $20m. Their aspiration, Branson says, was never more than academic. They would build a prototype – SpaceShipOne – fly it into space twice, and win the X Prize. This was a 2004 competition with a $10m prize for the first privately funded company to fly a reusable space ship into space twice. Then they'd retire SpaceShipOne to the Smithsonian, where it would end its days hanging from the ceiling. All of this did, indeed, happen. SpaceShipOne now hangs next to the Spirit of St Louis in the Smithsonian's Milestones of Flight gallery in Washington DC.

"And that was to be the end of it," Branson says. "Paul Allen is someone who loves to see what's possible, but he's not that interested in running a commercial business. So I went to see him at his house in Holland Park. I told him I thought he was missing a trick, and we would love to take it forward. So we bought the technology off him. We managed to get a group of engineers together and we started to build SpaceShipTwo."

Customers with Richard Branson in front of SpaceShipTwo. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer

Customers with Richard Branson in front of SpaceShipTwo. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer

SpaceShipOne had been filled with "single point failures". "If one bolt falls off and you die, that's a single point of failure," the Virgin Galactic engineer, Matt Stinemetze, told Wired magazine in March 2013. "There were things that you probably would've done differently if you're going to carry Angelina Jolie."

For SpaceShipTwo, Rutan's engineers had to turn the prototype into something that could go to space "100 times, maybe 1,000 times", Branson tells me. Developing the rocket motor has been the hardest challenge, followed by modifying the electric actuator – the mechanism that enables the pilot to move the stabiliser, the big part of the tail. SpaceShipOne had one. For SpaceShipTwo they built two in series, so one can fail and it will still work.

Every addition to the prototype needed to be as light as possible – any superfluous weight will eat into the already meagre weightless minutes. Within this constraint, they had to decide how many passengers to take. They settled on six and two pilots, and built a ship 1.6 times bigger than the original.

In 2004, even though they were still – they thought – three years from launching people into space, Virgin opened a reservations website. It crashed under the weight of interest. The first people to pay their deposits included George Whitesides, who back then was chief of staff for Nasa, Trevor Beattie and the Dallas actor Victoria Principal. The Virgin Galactic designers polled these early future astronauts. What did they want out of the experience? They wanted to see Earth from space. They wanted a really good view. So Virgin put in lots of windows. For the interior design they appointed Adam Wells, the man who invented the Virgin Atlantic flat bed and the purple mood-lit Virgin America cabin. He went for white and silver – colours that would "not draw attention to themselves and instead get out of the way of the incredible things happening outside the window".

Wells is telling me this by phone a few weeks later. He doesn't sound too happy about the white and the silver. "Longer term, I have ideas about how that might evolve," he says. "But we need to get up to space to see how those colours perform, what sort of behaviours people have with them."

There won't be much fabric on board, Wells adds, fabric being an unnecessary weight, and definitely no leather. "Leather would be a temptation for a high-end product, but it would be an odd thing to line the interior of your state-of-the-art spacecraft with a fellow earthling's skin." He pauses. "We think about this stuff a lot – about what's right and wrong."

Then he adds that everything he's telling me is "all under wraps".

"These are scoops?" I ask.

"Yeah," he says. "This is good info."

SpaceShipTwo won't have a flight attendant – there will be no drinks service or anything like that – and no toilet. Every passenger will be invited to wear a special astronaut nappy, or maximum absorbency garment, under his or her flight suit, which hasn't yet been designed.

"I met your sister Vanessa once," I tell Branson. "She told me you're psychologically different in some way. Like you have a restlessness – an itch that constantly needs scratching. Are you psychologically different in some way?"

He shifts in his chair. "I think that's possible," he replies. "I will feel guilty if I'm not trying to achieve something."

"So if a day passes when nothing's been achieved, do you see that as a bad day?" I ask.

Future astronauts at the Virgin Galactic spaceship. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

Future astronauts at the Virgin Galactic spaceship. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

"Definitely," he says. "Yeah. We weren't allowed to watch television as kids. We were told we had to be climbing trees or creating things. I'm sure that if I found myself watching television, I'd feel slightly uncomfortable."

"How long do you have to not achieve something before you start feeling guilty?" I ask. "An hour?"

"Oh, it's not very long," he says.

He glances at a painting on the wall of SpaceShipTwo in an attempt, I suspect, psychically to will me to remember what I'm supposed to be interviewing him about.

"Well, your psychological distress is for the benefit of others," I finish, "because you've really made my life better, especially with Virgin Atlantic and Virgin America."

"Fantastic," he whistles. "For a Guardian journalist to say that, particularly, thank you."

When our interview is over, I drive out of the Mojave Space Port towards Los Angeles. I pass the spot where, on a boiling hot afternoon – 26 July 2007 – Rutan's team was testing rocket propellant for Virgin Galactic when a tank of nitrous oxide exploded. There had been 17 people watching the test out here in the desert, this place for maverick engineers to push the boundaries. Shards of carbon fibre shot into them. Three of Rutan's engineers were killed, and three others seriously injured.

"It turned Burt Rutan from a young man into an old man overnight," Branson told me. "He'd never lost anybody in his life."

Rutan's company was found liable and fined $25,870. As the science writer Jeff Hecht wrote in New Scientist, "The company has an enviable reputation for creativity, but the report suggests it did not have an obsession with training, rules and written procedures… a dangerous combination when working with rocket fuels."

Rutan quit the business in 2011. He retired to the lakes of Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, a climate about as far from Mojave as is possible to find. He didn't respond to my emails asking for an interview.

When I asked Branson how personally connected he felt to the three deaths, he said, "Well…" Then he stopped. "If they were working directly for me, I would feel very responsible. Obviously, if we hadn't decided to do the programme in the first place, they would be alive today. So you realise that. But talking to relatives and survivors – I think every one of the survivors came back to work with the rocket company afterwards. Everybody had to pick themselves up and move forwards, and everybody did."

Paris Hilton is a future astronaut. So are Justin Bieber and Lady Gaga. Of course, regular aviation began this way, too, with the elite putting down the big money first. Ashton Kutcher is another future astronaut, as is Vasily Klyukin. He's a 37-year-old property developer and skyscraper designer from Russia. His ticket cost him just over £1m. He outbid everyone at an auction in support of Aids research at last year's Cannes film festival. The prize was a trip into space with a mystery companion, who turned out to be Leonardo DiCaprio.

"My desire was to win!" Klyukin emails me. "I am a man, and men had to win. Space is the Olympic gold medal in the 'Adventures' nomination and cannot be conquered by everyone." He adds that he was swept up in the glamour of the night, too – the auction was full of Victoria's Secret angels. But he has no regrets, no buyer's remorse. In fact, as a surprise for Branson, he's designed a Virgin Galactic-shaped skyscraper. He emails me a mock-up of how it would look next to the Gherkin in central London.

A Virgin Galactic-shaped skyscraper, designed by one of the future astronauts. Photograph: Vasily Klyukin

A Virgin Galactic-shaped skyscraper, designed by one of the future astronauts. Photograph: Vasily Klyukin

Then he unexpectedly invites me on a two-week transatlantic voyage on board his friend's 228ft super-yacht, the Sherakhan: "Very rare invitation! It would be two incredible weeks. Usually it costs a lot, about €1m [£850,000]." I consider his offer for a long time, but eventually decline, because frankly two weeks is a long time to be in the middle of the Atlantic with a Russian billionaire I don't know, and I think it would get awkward.

A week passes. I telephone Trevor Beattie to ask how his zero-gravity flight went.

"Um…" he replies. "OK. Where do I start? So. Being on the Zero G is like being flown in a hollowed-out Boeing over a hump. You float around uncontrollably for 30 seconds. Everyone does their swimming action, but it does no good. Then they shout an order: 'FEET DOWN! FEET DOWN!' That tells you you've got three seconds before the gravity comes back on and you splat back to the floor again. You try and get in a vertical position, so when the gravity comes on, you hit the deck ready for the next parabola. Which I very sensibly did." Trevor coughs. "Except, when I looked up, there was a bloke about two and a half times my bodyweight who was still floating 10ft above me at zero gravity. Then I realised I was in some kind of Wile E Coyote cartoon. There wasn't much I could do about it. The gravity came on and he came down like a fucking ton of bricks."

"Oh my God," I say.

"I tried to pull everything out of the way," Trevor says. "The only thing I couldn't extract was the end of my left foot, so I ended up with a fractured toe."

"Bloody hell," I say.

Ad man Trevor Beattie is in line to be one of the first space tourists. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

Ad man Trevor Beattie is in line to be one of the first space tourists. Photograph: Winni Wintermeyer for the Guardian

"Anyway," Trevor continues, "I didn't want to abort the flight, so I lumbered on. We did a few more parabolas. Then we came back. I had to get a taxi straight across town to LAX, so by the time the adrenaline wore off and I was on a 10-hour flight to London, I was a bit of a mess."

"This is hilarious," I say.

"The doctors thought so, too," Trevor says.

It's two weeks later. I'm sitting with Richard Branson in a hotel room in Washington DC. He is in town for a conference about the war on drugs. I'm here because my time with him in Mojave was short and there were many things I didn't have time to ask. Particularly, what will space travel on Virgin Galactic actually feel like? I can't picture it.

"Well, it's all in our imagination at the moment," Branson says.

Then he tries to explain.

It will all begin in the deserts of New Mexico, inside a spaceport,Spaceport America, designed by Norman Foster. The building is already finished (although the interiors are still to be done). The photographs make it look incredible – vast but almost invisible, as if it's growing out of the horizon, the same rust colour as the sand around it and the mountains beyond. It cost $212m – paid for by New Mexico taxpayers – and was built so far out in the middle of nowhere that they had to construct 16km of road just to connect it to the nearest tarmac.

Later, Virgin Galactic's Whitesides will describe the spaceport to me over the phone as "a welcoming cradle for this band of explorers, something sleek in the sense of 2001: A Space Odyssey, but friendly in the sense of the Virgin Heathrow lounge. People will see it and think, 'Yes, this is the place I should be flying to space from. This is appropriate.'"

Future astronauts will spend three days at the Spaceport for safety training and to pre-acclimatise themselves to the "sights and sounds" of space travel. "So you're not going to be doing everything for the first time on the flight," Adam Wells says. There'll be a simulator to reproduce the various thumps and bangs, "so when you hear some sort of clunking sound, you'll know it's because the landing gear has just gone up or down." Without all this, Wells says, there'll be "a real risk of sensory overload on the flight. You'll be bombarded with so much that's new to you, your memory won't be able to log it and fix it in place." And you'll come back to Earth remembering nothing much.

Also, during those three days, Wells's people will take your measurements, because "we're effectively rebuilding the seat for each customer". This is for the G-force part of the trip. It's much less unpleasant if the Gs are concentrated in your chest, so the personalised seat configuration will help with that. And then, on day three, you'll climb into SpaceShipTwo.

You will begin its flight attached to a plane with two fuselages – WhiteKnightTwo. It will feel like a normal takeoff and a normal flight until you reach 50,000ft. "At 50,000ft the sky is a much deeper blue," Whitesides tells me. "The vast majority of humanity hasn't been to 50,000ft. Anyway, you get up to 50,000ft and then you have the release and you'll feel a sense of instantaneous weightlessness as the vehicle drops away. That'll last a couple of seconds. And then the pilot turns the vehicle upwards and launches the rocket motor."

"Suddenly, then," Branson says, "you're going from zero to 2,500mph in eight seconds. That's going to be a rush you'll never experience again in your life. You'll go from tremendous noise, you'll feel it through your body, and then the absolute beauty comes when the motor cuts and it's just this total… silence."

"The instant that the rocket motor shuts off, literally everything inside the cabin becomes weightless," Whitesides says. "You're still going up at a tremendous velocity, but once that motor is off, the pilot will initiate the space phase of the mission. He'll tell people that they're able to get out of their seats and float around the cabin."

"The seating system reconfigures itself," Wells says, "so you don't have to think about putting the seat in the right position. It's going to do it itself. The customers' time is incredibly valuable while on this flight, and the last thing we want to do is burden you with responsibilities to move things around or to remember something or to handle something that would be tricky in any way. We want it to be completely intuitive."

"There are plenty of windows and plenty of room," Branson says, "and you just levitate out of your seat and float around and look back on Earth and you'll be one of only 500 people who have ever been into space."

"You'll reach the point of maximum altitude and start to come back down," Whitesides says, "like a ball being thrown up with one hand and caught with the other hand. Once you get closer – perhaps 30 seconds from atmospheric re-entry – you'll get above your seat and gently sink back down and put your seatbelt back on. And you'll get ready for re-entry." And then, as the Virgin Galactic website promises: "Later that evening, sitting with your astronaut wings, you know that life will never quite be the same again."

"So Trevor Beattie went on the Zero G flight the other day and a man was floating above him and then the gravity came back on and he fell on him," I tell Branson.

"A man fell on Trevor Beattie?" he says.

"He broke his foot," I say.

"Trevor did?" Branson says.

I nod.

"Oh dear," Branson says.

"Doesn't Trevor Beattie's broken toe show the dangers of what happens when the gravity comes back on?" I say.

He frowns at me. "We'll give you warning and make sure you don't get a broken toe," he replies. "Buzz Aldrin told me, 'Just enjoy space. Don't do the Zero G. With the Zero G, they put you through 15 parabolas. In space, you've just got one beautiful parabola.'"

One month later, I am about to become weightless in a hollowed-out Zero G plane in the air above Fort Lauderdale, Florida. There are no Virgin Galactic future astronauts on this flight. Instead, there are 20 or so honeymooners, retirees, vacationers. We lie on padded mats on the plane's floor, waiting for the weightlessness to start. When it does, it is at first bewildering. You suddenly levitate, as if you're in a magic trick. You're Sandra Bullock in Gravity, except instead of debris crashing into you, it's tourists from New Zealand and Brazil. There is chaos and injury potential. At the back are rows of airline seats. If you don't quickly learn to control your movements while you're weightless, you might drift over them and plummet when the gravity comes back on. We land on the mat with a very big splat.

Each parabola lasts 30 seconds. There are 15 in all – apparently the optimum number before people start to vomit (Nasa puts its trainee astronauts through something like 60 parabolas and violent retching is the norm). By the third parabola, you realise you are no longer bewildered. You can handle it. And that's when you become magnificent.

Jon Ronson in the Zero G plane.

Jon Ronson in the Zero G plane.

As I somersault, I remember something a Virgin Galactic future astronaut told me over the telephone last week. His name is Yanik Silver and his company, Maverick Business Adventures, organises adrenaline holidays for "exclusive" clients. The introductory video on its website makes it clear that you probably shouldn't put your name forward for one of Yanik's trips because he's very selective and you're "probably not right". It's solely for "entrepreneurs or CEOs or business owners who live life to the fullest and want to create incredible breakthroughs in their business… If you're a top-gun entrepreneur, there's not that many people who will understand you, and who better to go on those incredible adventures where success and high-achieving is the norm, instead of people secretly wishing you would fail?"

I think Yanik is in some ways a quintessential Virgin Galactic future astronaut. Back in Mojave, another CEO had told me that he considered being a space adventurer and being an entrepreneur to be much the same thing – with both, you need to leap fearlessly into the unknown, demonstrating a courage that others lack (although when I repeated that to Beattie, he laughed and said, "How self-important!"). Yanik takes his specially selected CEOs scuba diving between the tectonic plates in Iceland, and high-speed evasive driving, and on Zero G flights. He told me something miraculous happens to a business brain during those pumped moments: "You get new ideas, new pathways in your thinking." I asked him at what point the new ideas present themselves. Is it while you're plummeting to the ground before the parachute opens? He said no, it's usually back in the hotel bar later that night. Perhaps Yanik is right. Maybe I will get a new idea at some point later today. I am, after all, lost in the moment, which is rare for me. But then something unfortunate happens.

The Zero G on-board photographer beckons me to float towards him and the instant I concentrate on the manoeuvre the nausea begins. It is a cold, wet, overwhelming, hellish nausea. And it only gets worse with each subsequent parabola. The Zero G people would call this a successful flight, because no actual vomiting occurs. But I don't consider myself a Zero G success story. As I float in a clammy sweat and watch my fellow weightless people joyfully catch droplets of water in their mouths, I suddenly remember how – many years ago – a man had told me he'd taken part in group sex.

"What was it like?" I'd asked him.

He frowned. "Honestly," he said, "it's better to watch than to actually do." There are a lot of awkward physical realities involved, he explained. It's best to spare yourself and just spectate.

Will commercial space travel really be as safe and awesome as Branson says? Who'd have the experience to answer these questions without any of the vested interests? An astronaut. A non-aligned astronaut. So I telephone Chris Hadfield.

Hadfield is the Canadian astronaut who became famous for posting a video of himself singing Space Oddity during his five weightless months on board the International Space Station. I describe my Zero G experience to him. Is that what real space is like?

"Oh no," he says. "On the Zero G, you're weightless and then squished, and weightless and then squished. It's nauseating because it's cyclic. You said yourself that the first few parabolas were fine." Prolonged weightlessness, he says, "is just magic. You had it for 30 seconds and it's not very good weightlessness. The pilots do their best, but you still occasionally bang people off the ceiling, and it's still very short. To have it last for ever is so much fun. It's such a joy. So delight-filled. And then you look out the window and the whole world is pouring by at eight kilometers a second. So you've got the grace of weightlessness and the gorgeousness and richness of looking at the world. I loved every second of it."

"And the splatting?" I say. "Will there be lots of future astronauts with broken toes?"

"Oh, it'll be nothing like that," he says. "It'll be much more gradual. The upper edges of the atmosphere are very wispy. You will have seen the worst case on the Zero G from a nausea and a transition point of view."

I tell him how Branson had described Rutan's shuttlecock mechanism as "foolproof", and said that the pilot could be "sound asleep on re-entry and it didn't matter".

There's a short silence. "Hmm," he says, sounding doubtful. "He's right – it is a simple, rugged mechanism that is reusable. It's a nice, elegant solution. It's a good design. But it's not risk-free, and it's complex. They're working very hard – they've got experienced engineers and pilots to make it as safe as possible. But to come into any programme with any vehicle and think you're somehow immune from what everybody else has always experienced with every machine in history is unrealistic. They don't know everything yet. They still have a lot to learn. If they fly it 100 times, maybe they can be careful and judicious enough to avoid a crash. If they fly it forever, eventually one of them will crash. That's just statistics. It could well be something that nobody anticipated. That's normally how it happens with complex machines." He pauses. "I'm just being realistic."

I ask if he thinks the future astronauts will enjoy their experience.

"They'll go very, very fast," he replies. "That'll be really thrilling. They'll see directly with their own eyes something that very few human beings have seen: what the world looks like from above the atmosphere. But if they think they're going to see the stars whipping by, or they'll be going around the world several times, then they're incorrect. And they're going to be disappointed." He pauses. "I went around the world something like 2,500 times. I saw thousands of sunrises and sunsets and all of the continents. Whereas this vehicle will go straight up and straight down again. That doesn't belittle anything. They'll get some of the same views. But it's a different experience."

I think Hadfield is concerned he is maybe sounding too sniffy, because now he says, "Richard Branson and his team are being very brave. Both financially and from an exploration point of view, they're trying to do something nobody has done before. This is brand new." He says that as long as the future astronauts manage their expectations, as long as they "plan for it, ask themselves, 'What am I going to do with my minutes of weightlessness?' so they don't come down and say, 'Huh. That's not what I was expecting', they're going to love what's happening."

Two weeks later I receive an email I hadn't expected at all: "I am in Buenos Aires on vacation. I will be at home in Idaho on Saturday and happy to talk to you after that."

It is Burt Rutan.

I call him the day his cruise docks – this semi-reclusive engineering genius. I say that future generations might regard him as the Brunel of democratised space travel; does he think about things like that?

"Only since my retirement…" he says. He's got a rich, deep American-South voice. Then he tells me why all this began for him.

"In the mid-60s, a friend of mine, Mike Adams, got killed during a re-entry." They had been stationed together at the Edwards Air Force basein Lancaster, California, when Adams, test flying an experimental suborbital plane called the X-15, "didn't line the angles up. He was killed because the requirement to do a precision re-entry had not been met."

Adams's death stayed with Burt, he says, even when he left the air force and set up business in a hangar at the Mojave airport, designing prototype planes. "It was just a deserted old second world war training airport in a crummy little desert town. I had a family, which I lost mainly because I was a workaholic." He says most aerospace engineers work on an average of two-and-a-half planes during their whole careers. He was building one every year, "without ever injuring a test pilot. You can't have more fun than a first flight when you find out if your friend lives or dies flying it. And I flew six first flights myself. With a tiny crew of three dozen people who worked their asses off."

He says you won't find his inventions in the big airliners – the Boeings and Airbuses. They're overly risk-averse and conservative, which is why their planes look identical. But the private jet companies have embraced his creations – planes such as the Beech Starship. And throughout it all he brooded over the death of Mike Adams and wondered how he might invent "carefree re-entry".

He says there was no great Eureka moment with his shuttlecock idea. But one day he felt confident enough to approach Paul Allen and say, " 'I would now put my own money into it if I had the money.' And he put out his hand and we had a handshake. That was the extent of the begging for money I did for SpaceShipOne. He gave me several million dollars and said, 'Here. Get going.'"

"What's Paul Allen like?" I ask.

"Opposite of Sir Richard," Burt replies. "I could call Sir Richard while he's sleeping at home in Necker island and chat with him. We debate global warming fraud all the time."

"Hang on," I say. "Which of you thinks it's a fraud?"

"He thinks it exists; I think it stopped 17 years ago," Rutan replies. "Anyway. Paul Allen's own people can't just walk into his office. They schedule a meeting a couple of weeks in advance. On the few occasions I was alone with Paul, his own people would rush up to me and go, 'What did he say?' But if he says something, everybody listens, because it's an important thing to be said."

Between 2001 and 2003, SpaceShipOne was a covert endeavour. Nobody outside Burt's weather-beaten hangar knew they were "developing all the elements of an entire manned space programme. We developed the launch airplane, the White Knight. We developed our own rocket engine, and a rocket test facility, and the navigation system that the pilot looks at to steer it into space. We built a simulator. And, of course, we built SpaceShipOne and trained the astronauts. In 2004, we flew three of the entire world's five space flights – funded not by a government but by a billionaire who made software. This private little thing. Later, people said I must have had help from Nasa. I didn't want Nasa to know. And they didn't."

Since then, Rutan says, history has proved his shuttlecock mechanism to be foolproof. "People told me it would go into an unrecoverable flat spin, but I knew in my gut it would work. And it worked perfectly the first time and every time. It has never had to be tweaked or modified. Which is crazy, because it's so bizarre."

Any delays these past 10 years, he says, have been due to the complexity of the rocket motor design and the fact that Virgin Galactic is full of "smart people" – by which he means committees: interior design committees, PR committees, safety committees. He sounds a bit rueful about this, like if they had listened to him, it could all have gone a lot faster.

He doesn't mention the accident. I'm not relishing asking him about it, because I'm sure it was the worst day of his life, but when I do, he immediately says, "Sure, I'll talk about that."

He won't go into its cause much – only that it was a "very routine" test that fell victim to "a combination of some very unusual things". He pauses. "All of us would be bolt upright at two in the morning for a while after that." And even though he was 220 miles from the explosion, the shock almost killed him, too. "My health deteriorated to where I could almost not walk. I just seemed to get weaker and weaker every day." He says that if I saw pictures from the unveiling of SpaceShipTwo at the Museum of Natural History in New York that following January, I'd see a man "incapable of walking up three or four steps". (I do see those pictures later and he does looks terrible.) Eventually his condition was diagnosed as constrictive pericarditis – a hardening of the sac around the heart. He says that as an engineer he can't bring himself to believe that the stress of the accident hardened a membrane: "That wouldn't make sense." But his wife is convinced of it.

At the end of our conversation, Rutan suddenly says, "If there's an industrial accident at a corporation and three people are killed and three people are seriously injured, how often is there a lawsuit where the families sue the company?"

"Almost every time," I say.

"There was none," he says. "There was none. We wrapped ourselves in the families. We told them the truth from the start. None of them sued us. Each of those families is a friend of the company. And that has a lot to say about something that I'm most proud of in my career, and that is how to run a business from an ethical standpoint."

Later, I look at the memorial website for one of the men who died, Eric Dean Blackwell. It is maintained by his wife, Kim. At the bottom there's a link to Virgin Galactic, so people can read updates on how the programme is progressing.

Back in Mojave, I'd mentioned to Branson that 10 years earlier I'd read the critical Tom Bower biography, Branson, and that when I later asked Bower if he had anything good to say about Branson, he replied, "No."

"Oh, he's forecast our financial demise," Branson replied. "The thing is, he got a bit lucky with Robert Maxwell and everyone he's done since then he thinks is in Robert Maxwell's clothing."

Last month, there was a flurry of Tom Bower activity. He's written a new book, Branson: Behind The Mask, in which he claims that Virgin Galactic is a "white elephant" with no licence to fly into space and no rocket powerful enough to take passengers anyway. I email Branson's people. They reply with a statement that the rocket motor has "burned for full duration and thrust multiple times" during tests, and that they expect to receive the full licence "well in advance of commercial service. Richard," they say, "remains extremely confident of a 2014 launch."

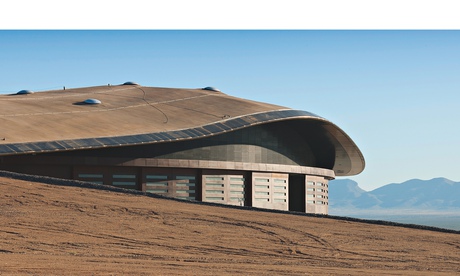

The $212m Norman Foster-designed Spaceport America in New Mexico, where astronauts will train for three days ahead of their flight. Photograph: Courtesy Nigel Young/Foster & Partners

The $212m Norman Foster-designed Spaceport America in New Mexico, where astronauts will train for three days ahead of their flight. Photograph: Courtesy Nigel Young/Foster & Partners

Branson hopes that his future astronauts' five weightless minutes will be only the beginning, and that "suborbital point-to-point travel" is next. This means a journey on SpaceShipTwo that will actually go somewhere, and not just up and down. They could fly from London to Australia in two-and-a-half hours, Branson tells me. And then there are the satellites. "We can put up 15,000 satellites over a six-month period," he said, "which is more than there are up in the air today. For the three billion people who are in the poverty trap, they're likely to get access to mobiles and internet for a fraction of what it now costs."

And this, Branson insists, is imminent. A test flight into space – empty of passengers – will happen in the next few months (Virgin are vague on the details). And the first six astronauts, including Branson and his children, Sam and Holly, should be up later this year. The inaugural flight will be televised live by NBC. The TV company has put out a press statement about it: "Without a doubt, Sir Richard and his children taking the first commercial flight into space will go down in history as one of the most memorable events on television."

Branson told me back in Mojave that his "eyes are open" about making his family the guinea pigs. "Everybody who signs up knows this is the birth of a new space programme and understands the risks that go with that," he said. Then he paused. "But every person wants to go on the first flight."

No comments:

Post a Comment