7 Ways The Pioneers Preserved Food Without Electricity

7 Ways The Pioneers Preserved Food Without Electricity

Written by: Steve Nubie How-To

The pioneers knew more than a few tricks to preserve food for the long-term. Any form of food preservation was designed to kill and inhibit the growth of bacteria, fungus and other micro-organisms. It also was designed to prevent the oxidation of fats which could lead to rancidity.

Our pioneer ancestors needed to master these skills for two reasons:

1. The seasons. Summer and fall were times of plenty, but winter and early spring were not. The ability to preserve food to over-winter in many environments was vital to survival.

2. Long journeys. They were traveling across open prairies in a wagon train, traveling on sailing ships to distant shores, traversing mountains with little or no vegetation or wildlife. Long journeys required stores of food that would keep well and not cause sickness due to foodborne illnesses.

Plan Ahead – or Else

You may have heard of the Donner Party. They were pioneers traveling to California who were trapped in the Rocky Mountains during relentless blizzards and cold temperatures. Many slowly starved to death while others resorted to cannibalism. That’s poor planning.

We’re not going to cover the obvious, like canning in mason jars (our pioneer ancestors didn’t have a lot of access to glass or finely crafted metal lids). And they certainly didn’t irradiate foods or use electric dehydrators.

Here are seven ways the pioneers preserved food:

1. Salt. Any civilization living next to a saline or salty body of water had the ability to dehydrate the water and gather salt. In ancient times, it was a valuable commodity and for a while, Roman soldiers were paid their wages with salt.

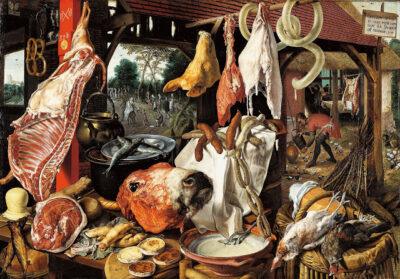

While we tend to think of salt as a standard seasoning, the value of salt in ancient times was more related to the preservative power of salt. Salt reduces moisture, inhibits bacterial growth and leaves a flavor that’s easy to eat, depending on the salt level. Ships at sea often carried small barrels of pork embedded in a cask of salt or a salt brine. This “salted pork” was standard fare for many people traveling across oceans for long journeys.

Salt is often used in brines to enhance the preservation of fish, fowl and game before drying or smoking, and it’s a standard addition to most pickling recipes and those casks of salted pork.

2. Fat. This may come as a bit of a surprise but fat, especially beef feet or tallow and suet, has exceptional preservative properties. It’s a standard addition to pemmican recipes, which usually involves a 50 percent mix of dried and powdered beef or buffalo and an equal amount of fat plus some raisins or black cherries.

Also, pioneer women would often take cuts of meat and place them into a crock or small barrel and top it with tallow or suet due to its preservative properties. On a fundamental level, the congealed fat is preventing oxygen and airborne microbes from reaching the meat. It was important to keep any container with these combinations sealed from air.

Also, pioneer women would often take cuts of meat and place them into a crock or small barrel and top it with tallow or suet due to its preservative properties. On a fundamental level, the congealed fat is preventing oxygen and airborne microbes from reaching the meat. It was important to keep any container with these combinations sealed from air.Many of our pioneers preserved their most valued cuts of meat in honey and like salt, it added a pleasant taste to the food when eaten.

4. Vinegar. This is perhaps the most potent, natural antiseptic you can safely consume. It’s actually acetic acid and is usually a 4 to 5 percent solution in water. It was also easy to make from various fruits like apples. It was used to preserve everything from vegetables to fruits to meats, fish and fowl.

The typical process involved immersing the food in vinegar in a cask or container, and sometimes salt was added for flavor and additional preservative qualities.

5. Drying or dehydration. This is probably the oldest food preservation technique. It was used to preserve everything from vegetables to fruits and of course meats, fish and fowl.

The critical success factor with drying foods is to remove as much moisture as possible.

- Beans or legumes were often strung on sticks and hung in the rafter of a cabin or tepee to air dry.

- Fish were filleted and often salted before being hung in the sun on racks or over smoldering fires.

- Strips of meat from game were sliced thin, salted if possible and also hung in the sun or over a fire to dry.

- Fruits were sliced thin and left to dry in the sun and taken indoors at night to continue the drying. They were turned often and sometimes smoked. They, too, were hung on sticks in the rafters at times.

- Fairly consistent temperatures in winter and summer.

- Consistent humidity, which is beneficial to root vegetables.

- Protection from insects and animals, to some degree.

- Protection from sunlight.

- Easy access to a variety of vegetables

- Smoking fish, fowl and game over a low and slow draft of smoke in an enclosed space not only dried out the food, but the smoke and moderate heat both killed and inhibited bacterial and fungal growth.

Even after removal from the smoke house, large pieces of smoked meats would last a long time if kept in a well-ventilated and cool and dark place. Parma hams in Italy hang for months and months in the cool towers of buildings after careful brining and smoking.

Conclusion

Do more research about food preservation and if in doubt, throw it out. Our pioneer ancestors learned the hard way about what worked and didn’t work.

http://www.offthegridnews.com/how-to-2/7-ways-the-pioneers-preserved-food-without-electricity/

No comments:

Post a Comment