BITTER DISSENTS IN GAY MARRIAGE CASE LAY BARE DEEP DIVIDE IN HIGH COURT- AND IN AMERICA

Interns with media organizations run on Friday in Washington with copies of the Supreme Court decision that the U.S. Constitution gives same-sex couples the right to marry. (Photo: Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

Justice Anthony Kennedy almost always votes alongside his four conservative colleagues on the Supreme Court. But when he doesn’t, it’s often in big, transformative cases, like Friday’s gay marriage decision. His defection clearly has made his conservative peers hopping mad.

Each of the four conservative justices in the minority wrote his own dissent, a sign that their disappointment and anger at the decision striking down gay marriage bans could not be combined into one response. Separately, their writings bordered on the caustic, sometimes even making personal attacks on Kennedy’s jurisprudence and writing style.

Kennedy, who is known for rhetorical flourishes and sweeping legal writing, begins his opinion with a broad statement: “The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity.” He concludes that the 14th Amendment guarantees the right to marriage to same-sex couples, and that denying them marriage robs them of liberty entitled to them by law. And on his way, Kennedy colorfully explains that marriage is an ennobling institution that bestows dignity upon those who enter it. (“Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there,” Kennedy writes.)

The opening seemed to enrage Justice Antonin Scalia, who went even further than usual in his criticism of Kennedy’s signature flowery language. He wrote in a footnote that he would “hide his head in a bag” if he ever signed onto an opinion containing this first sentence, which he said contained “the mystical aphorisms of a fortune cookie.”

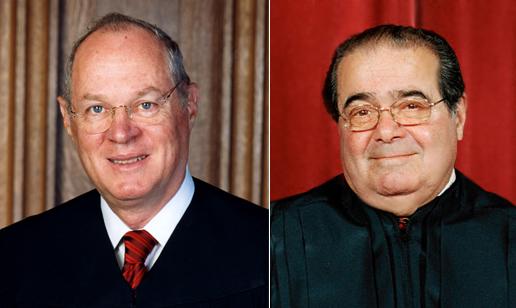

Justices Kennedy (left) and Scalia. (Photos: U.S. Supreme Court via Wiki Commons)

Chief Justice John Roberts, who read much of his dissent aloud from the bench, a sign of his deep displeasure, called the opinion’s reasoning “unprincipled.” He even compared it to the infamous Dred Scott case from the 19th century, when the Supreme Court held that no one of African descent could be an American citizen.

Conservative judges also lambasted Kennedy for skipping some key legal details in his opinion, such as what level of scrutiny the high court used to examine gay couples’ claims.

Doug NeJaime, a professor of law at UCLA, says that conservative justices have long criticized Kennedy’s opinions for this sort of gloss-over when he writes with the liberals. “This is classic Justice Kennedy,” he said. “It’s not the kind of mechanical, constitutional analysis that some of the other justices might want.”

Complaints about Kennedy’s writing style pepper the dissents. Roberts mocks its “shiny rhetorical gloss,” Scalia calls the opinion’s style “pretentious” and full of “silly extravagances.” Justice Clarence Thomas objects to the majority’s characterization of marriage as ennobling. “I am unsure what that means,” he wrote. “People may choose to marry or not to marry. The decision to do so does not make one person more ‘noble’ than another.” At one point, Scalia even goes line by line through parts of the opinion, adding critiques in parentheses, such as, “Huh?” and “What say?” He ends by declaring that the opinion will “diminish this Court’s reputation for clear thinking and sober analysis.”

Perhaps most striking was when Roberts went so far as to tell gay people in his dissent that they should not celebrate the Constitution today, because that document had nothing to do with their legal victory.

The statement gets to the heart of the conflict between the majority and the minority in today’s decision: Whether the Constitution is a living document that evolves with the times or whether it is frozen in the 18th century. Though Kennedy generally sides with his conservative colleagues who more strictly interpret the Constitution, he has argued for a more expansive interpretation of the document in this case as well as in Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down state laws that criminalized sodomy.

“The nature of injustice is that we might not always see it in our own times,” Kennedy wrote in Friday’s opinion. “The generations that wrote and ratified the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment did not presume to know the extent of freedom in all of its dimensions, and so they entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.”

Kennedy thinks we are still learning this meaning. His colleagues do not.

No comments:

Post a Comment